District enrollment rules conspire against equity from top to bottom. Even those most “fair” mechanisms like lotteries. Redistributing opportunities and privilege means upending these rules, something Oakland Unified has started, and gotten huge pushback on. But it’s time we take a hard look and make some hard choices. I agree with president Harris’s comments at the recent OUSD meeting that for too long Black students have been “locked out” of Oakland opportunities, and it’s time we change that.

So let’s look at how enrollment happens. First you enroll in your district of residence. As Ed Build noted, many district boundaries create gates of privilege—look at Oakland, within Oakland is Piedmont—its own district, those kids get 5k more than kids across the street in OUSD, and 2% of those students are poor. So if you can afford to live in one district yards away from another you get a lot more.

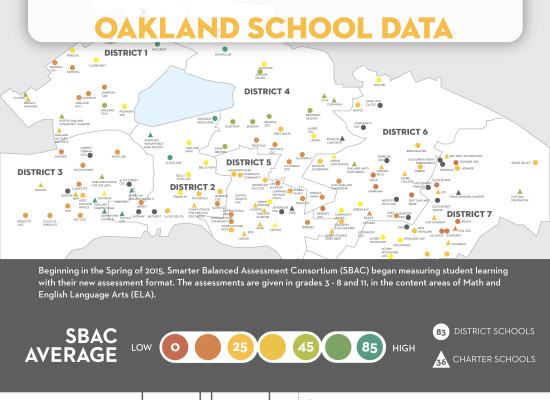

Then look at neighborhood boundaries, most of OUSD’s top scoring schools are in neighborhoods with average home values in the million dollar range, so if you can’t afford to live there, you don’t get those schools. And even to go to an out of neighborhood school, you can really only access those if you have transportation, which again privileges some and disadvantages others. Take look at the map of school performance—you have very different odds of attending a green school based on where you live.

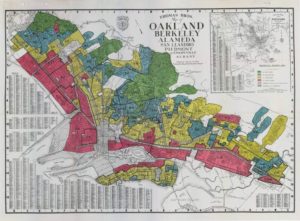

And, these neighborhoods aren’t random, they were created by racist redlining practices. Check out this historic map of Oakland’s redlining (the practice of not providing loans to Black and Brown people).

Any correlations there between where they allowed us to live and the school quality?

So there is nothing natural about our neighborhoods, they were designed to be exclusive. So assigning schools on that basis perpetuates that exclusion.

What could be more fair than a lottery?

Even the “most fair” mechanisms like lotteries and waitlists hurt disadvantaged kids.

Lotteries require folks to put in a timely application often six months before school starts, so newcomers, kids that are moving mid-year, and the less informed tend to miss them. Same issue with waitlists. First come first served, disserves newcomers or latecomers—and those are students who tend to have greater needs.

The heart of the matter

The big issue is the supply of high quality schools and who gets access to them. We don’t have enough high quality seats to meet the demand for them, so the question becomes who gets them. Right now, the system privileges the more privileged. This should not be a surprise, despite frequent equity talk, very few have ever walked the walk. And even fewer will give up their privilege.

There are small changes we can make; reserving seats for newcomers or latecomers, giving preferences for diverse students, providing greater transportation, or doing away with ranked waitlists and just doing a lottery for each opening—without regard to when someone applies. The issue is ultimately one of will though, and a conscious redistribution of privilege.

As president Harris stated at a June board meeting, “we have been locked out” talking of the lack of access of Black families in East Oakland to high quality schools. We know this. We also know how to fix it, but when push comes to shove, and the din of the loudest and most privileged and empowered voices drowns out those who have been locked out, will we have the courage?