A guest post from Jeremy Gormley

Since George Floyd’s murder, a number of news articles have pointed to the contrast between Floyd’s upbringing and that of the police officer who killed him, Derek Chauvin. While Floyd grew up in a largely poor, racially segregated Houston neighborhood, Chauvin grew up in a mostly White St. Paul suburb.

In 1990 – approximately when Chauvin attended high school – the district’s median school percentage of Black students was 1.3%. Chauvin’s school, Park High School, had 25 Black students out of a student body of over 1,800.

Research points to the negative impact of school segregation on children’s racial perceptions, especially in earlier years. In fact, children may be the most racially segregated “at the very ages when they are developing racial attitudes.”

The mere possibility that Chauvin’s racially segregated schooling shaped his views of Black men like Floyd requires school districts to take a thorough evaluation of school segregation and its inherent dangers.

—

Oakland has a racially and socioeconomically segregated school system.

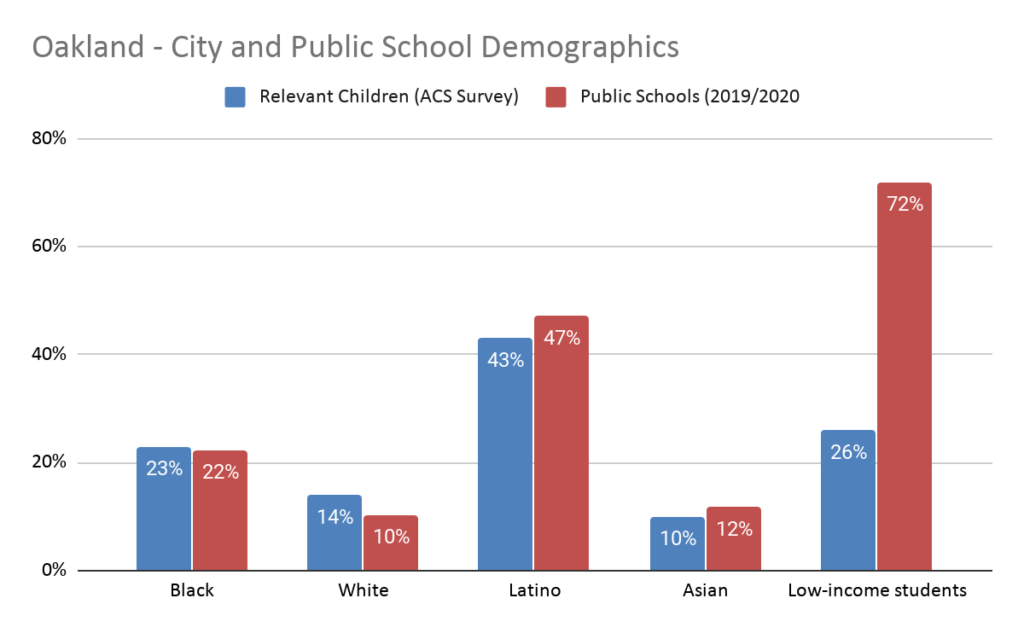

While the city itself is segregated along similar lines, it’s well documented that Oakland as a whole is quite diverse. Below are the demographics of relevant school-age children in Oakland: [1]

The differences between the racial breakdown of relevant children in the city compared to those in the district may not seem significant. But about 30% of White families are not enrolled in Oakland public schools (compared to about 10% of all other racial groups), while a disproportionate share of students in poverty are enrolled. [2]

More consequential, perhaps, is that most Oakland schools do not maintain the percentages we see above.

Oakland has 118 public schools, but 65 schools (55%) served over 80% low-income students in the 2019/2020 school year. Moreover, these high-poverty schools served 61% of all Black and Latino students in the district, but only 8% of all White families.

CCPA, for instance, enrolls approximately 95% low-income students and 93% Black or Latino students. Another 6-12 school, Oakland School for the Arts, on the other hand, enrolls 16% low-income students and 37% Black or Latino. [3]

Oakland’s uneven distribution of poverty across schools is highly inequitable.

High-poverty schools are largely difficult learning environments for both students and staff. The conditions associated with poverty often create health, learning, and emotional challenges for students. In Oakland, where around 40% of low-income students are English Learners, language is also a major barrier for many students. The more students with these challenges in a school, the more stress students and staff as a whole feel.

High-poverty schools also tend to be poorly resourced, offer less learning time, and see more teacher turnover. In district-run schools in Oakland, for instance, only around 38% of teachers in schools with more than 85% low-income or English Learner students are at the same school after 3 years, on average. For schools with less than 70% of the same population, 63% of teachers are returning in that time span.[4]

High-wealth schools are also problematic, especially in a district with over 70% low-income students. Schools with a disproportionate share of wealthier families tend to concentrate resources – from PTA funding to more experienced teachers – which creates an inherent imbalance of resources and programming across the district.

As the numbers in the graph above show, Black and Latino families disproportionately face the challenges of high-poverty schooling compared to White families.

All students, however, could benefit from more racially and socioeconomically integrated schools. Diverse schools have shown to reduce racial achievement gaps, and improve drop-out and college attendance rates. Moreover, all students benefit from reduced racial bias, leading to “greater mutual respect, understanding, and empathy across racial lines.”

—

As the death of George Floyd reminds us, a segregated society makes us captive to stereotypes which too often means White people bringing harm to Black families and communities of color.

To help combat this, Oakland must redefine its values and prioritize diversity in schools.

School diversity, just like funding and staffing, is a vital resource. When the district and its leaders make no effort to advance this resource, the segregated system we are left with is not by accident; it’s a choice Oakland is making.

—

Jeremy Gormley is an education activist and former teacher. He lives in Oakland and can be reached at [email protected]