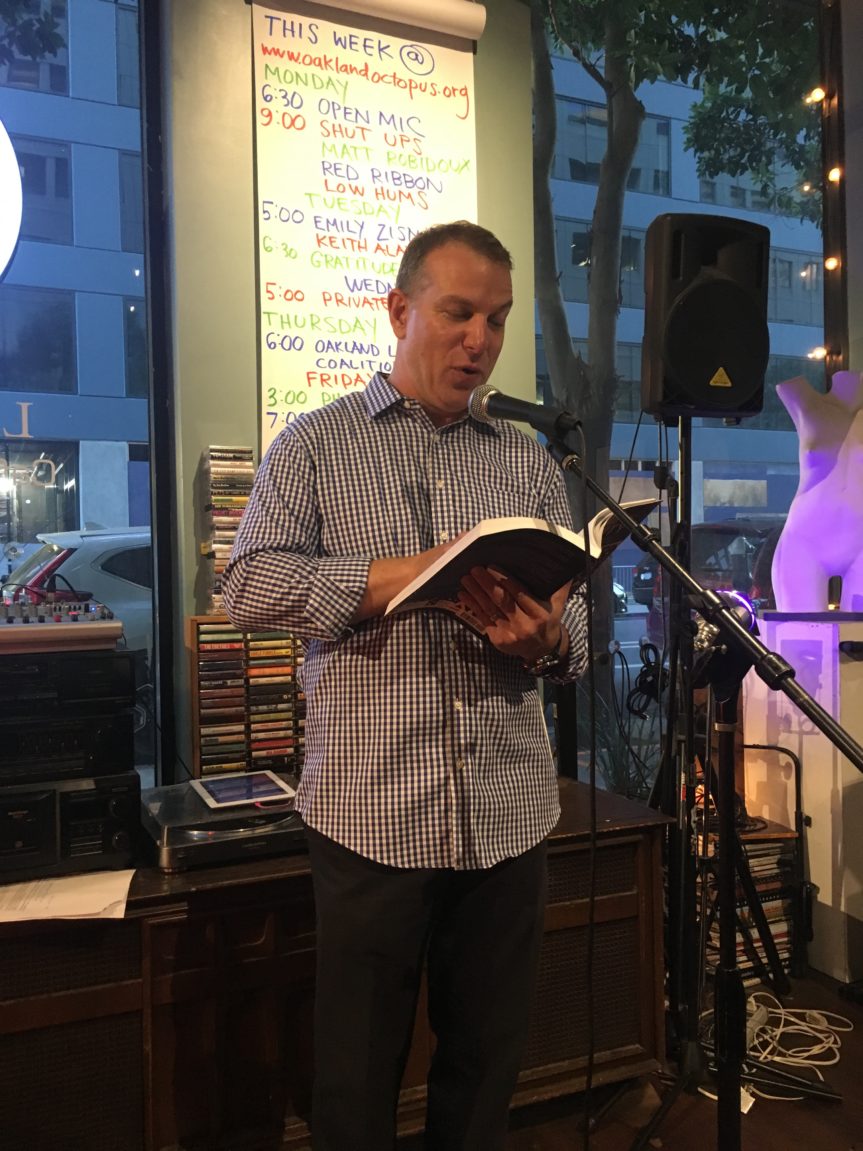

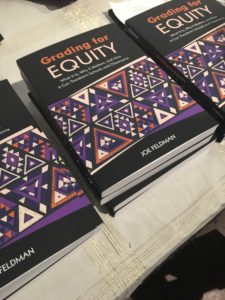

Joe Feldman‘s new book, Grading for Equity disembowels the way we grade students, hanging the entrails to show how inequitable and really illogical our present grading practices are, and how we can improve them– which he has been doing in real life for years with schools, it’s a must read for educators and those who want to improve how schools function. After his book launch in Oakland, we discussed the book and his work.

What is/are some of the key takeaways from your new book Grading for Equity?

Feldman: Despite our deep commitment to making our schools equitable, students are often grading in ways that undermine equity, thwart effective teaching and learning, and perpetuate long-lasting historical inequities in achievement. By critically examining the history of K-12 grading and implementing grading practices that are more accurate, bias-resistant, and motivating, we can reduce D/F rates and grade inflation and better promote equity in our classrooms and schools. The success of more equitable grading practices have been proven across hundreds of teachers and thousands of students throughout the country.

What’s wrong with the way we “grade” right now and what are some of the equity issues? You raise homework as an issue, can you explain?

Feldman: Because grading is rarely if ever included in teacher graduate training, onboarding, or in professional development, most teachers have no choice but to grade how they were graded, thereby replicating what are inequitable, inaccurate, and demotivating approaches to describing student learning and inadvertently perpetuating the achievement and opportunity gaps. For example, take the common practice of including a student’s performance on homework in the grade. Students are much more likely to complete homework if they have a quiet, well-lit space to work and college-educated parents who have the knowledge and availability to help (or if not, a paid tutor). By contrast, students are much less likely to complete homework if they live in a noisier apartment, have parents who didn’t graduate from high school, have jobs in the evening, or their first language isn’t English. Plus, nearly one-fifth of students report that they are unable to complete homework because they lack internet access at home. When we include homework performance in the grade, we add points to the grades of students with resources and deny points to the students who don’t. We translate the economic disparities into achievement disparities, replicating in our classrooms the very achievement disparities we want to interrupt.

“Averaging student performance is…mathematically unsound as well as inequitable”

Another example is the traditional practice of averaging a student’s performance over time, which is both mathematically unsound as well as inequitable. A student who struggles with content initially (earning Ds and Fs) but ultimately masters it by the end of the term (earning As) will have her performance averaged over the term (C). Her averaged performance will be lower than her actual achievement at the end of her learning, and therefore her grade will misrepresent her level of content mastery. Averaging is a mathematically flawed method of calculating grades and one that obscures student improvement. However, averaging also perpetuates inequities.

The student who doesn’t struggle early in a unit but instead gets high marks from the start—and therefore is not negatively affected by averaging her performance over time—did well because she obviously had prior successful learning experiences with that content before the unit even began. Perhaps she participated in an enrichment program the previous summer or she was enrolled in a tutoring service with an instructional program that anticipates the school’s curriculum, or perhaps she didn’t have disruptions in her life when the previous year’s teacher taught her essential pre-skills. These advantages enabled her to demonstrate high performance throughout the unit, which makes averaging a student’s performance over time a neutral policy that is much more likely to harm students who are new to the content or who have had less successful learning experiences. When we don’t average a student’s performance over time but more equitably consider a student’s final learning in the grade, we not only accurately describe a student’s level of content mastery; we level the playing field, allowing all students to be successful regardless of their resources and histories.

The Role of Implicit Bias in Grading

Traditional grading doesn’t just perpetuate structural inequities; it also is susceptible to our implicit biases. Most teachers include in their grading a “Participation” or “Effort” category that reflects the teacher’s subjective evaluation of a student’s behaviors, which we can’t help but judge through a biased lens. We know from research that in classrooms taught by white teachers, black students are typically rated as “poorer classroom citizens” than their white peers based on the types of behaviors often included in graded categories of “Participation” and “Effort”. When we include in grades a Participation or Effort category that is populated entirely by subjective judgments of students’’ behaviors, we are inviting our biases to infect our judgments. Awarding points for behaviors imposes on our students a culturally-specific definition (usually defined by the dominant culture) of appropriate behavior and interprets their behaviors through an unavoidably biased lens. Just as we might require students to write their name on the back of a test to prevent our opinions about students from infecting our grading of the test, equitable grading inoculates our grading against our biases by excluding student behavior from the grade.

You write about the subjectivity of grading and the inequity very convincingly, you also showed how much these grades matter for student opportunities, could you talk about that some?

Feldman: Grades drive major decisions about our students–decisions that affect their life trajectories–from course placement, promotion and athletic eligibility to college admission and financial aid. The psychological effect of grades on a student’s sense of self and relationship to school is enormous. Grading is implicated in nearly every instructional decision a teacher makes in a class: Do I grade this or not, and if so, for how much and with what consequences? However, the irony is that despite how interwoven grading is into the fabric of every student’s and teacher’s school experience, grading is rarely discussed in schools because it is so deeply connected to teachers’ sense of professional identity and autonomy.

What experiences made you dig so deep on grades and grading?

Feldman: For 20 years I was a teacher, principal, and district administrator, and something that always nagged at me was that you could have two teachers—let’s say they both teach 9th grade algebra–in the same school and maybe in adjacent classrooms, using the same textbook, have the same training, and their students are similar. One algebra teacher could have 10% of her students failing, and the other could have 40% of her students failing, and it’s only because they have different grading policies. I knew that wasn’t right–we want grades to reflect what students know, not reflect how their individual teacher grades. Then I researched more and saw that the problem was actually much more complex and widespread. Teachers who were using the best culturally responsive practices in schools that were entirely dedicated to equitable opportunities for students were using grading practices that were mathematically unsound, were highly subjective and biased, that demotivated students, and that actually undermined the equity work these teachers had devoted their professional lives to. I wanted to equip teachers and schools with a vocabulary, history, tools, and theories that would help them align their grading with their vision for equity, and to recognize how quickly these improved practices could significantly improve their work.

If you could offer a couple of pieces of advice to educators what would they be?

Feldman: We need to have the courage and partnerships among teachers, administrators, and parents/families to examine traditional grading and to make it more equitable. Some of the strategies, including excluding student behavior and homework performance, will challenge us about what we think we know about our students and motivation. For example, we might think that if we don’t give points for a task or an expectation, students won’t be motivated to do it. This belief–that students are best managed and incentivized by extrinsic rewards and punishments–is an artifact of when this grading system was created during the Industrial Revolution, when Skinner showed us how he could gets rats to change their behavior with food pellets or electric shocks. We now know that extrinsic motivation is a terrible way to motivate people to perform complex skills such as learning, yet we continue to use the language and currency of “points” in our grading (and complain when students are only concerned about points and not about learning). Equitable grading means letting go of extrinsic motivation, and even some of our beliefs about our students, and making our classrooms about learning and student progress where students are intrinsically motivated to learn and have greater ownership over that learning.

Do you want to get rid of grades, where does this work go?

Feldman: This isn’t about getting rid of grades; it’s about using the A-F letter system to report student academic progress more accurately, that motivate students intrinsically, and in ways that interrupt the cycle of achievement disparities.

Many of us enter the education profession because of an emotional conviction that every student deserves a full opportunity to succeed. When we explicitly connect grading to equity and teachers learn how traditional grading practices undermine the very equity they want in their classrooms, they have the urgency and the persistence to learn more, to push through skepticism and discomfort. Nearly every school’s and district’s goals include a commitment to equity, which makes the importance of tackling grading more obvious and justifiable. Explicitly naming the inequities in current grading and how grading can promote equity means seeing beyond grading improvements as a nice-to-have pedagogical shift; we have a moral imperative to dismantle the inequities that endure in our schools, and we’ll never make good on our promise give every student a real chance at success until we make our grading equitable.

Intro: Joe has been a high school teacher in Atlanta Public Schools, assistant principal in NYC, principal of a charter high school in Washington, DC, and Director of K-12 Instruction in Union City, CA. In 2013 he founded Crescendo Education Group, which partners with schools and districts to improve the accuracy and fairness of teachers’ grading practices. He now works with teachers throughout the country, has teamed with teacher education programs, and presents at national educational conferences. He has published numerous articles on grading and equity, and his book, Grading for Equity, has just been published by Corwin (download the Prologue and Chapter 1 here). He lives in Oakland with his wife and two children.

Conclusion: For more information, see gradingforequity.org, and check out the online course on equitable grading starting in January 2019.

Feel free to reprint.

—

650.793.9393