A guest post from Families in Action

“When one of our biggest concerns about closing schools is that we have so many students who won’t have access to a warm, safe, dry place to be for 8 hours and won’t have food to eat, we really need to think about what the hell we’re doing in this country.”

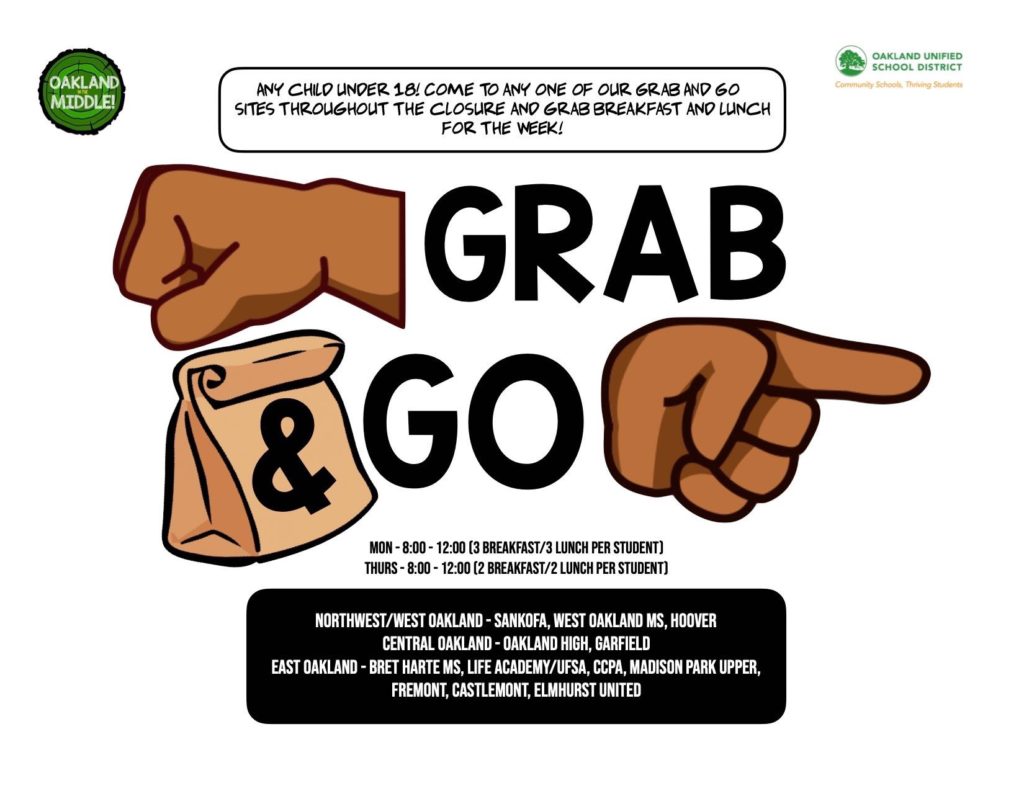

On Monday — hours before the “shelter in place” announcement went out to most of the Bay Area — the nutritional staff at Elmhurst Middle School served 2,000 meals for the children of East Oakland.

They gave out premade sliders and sandwiches; breakfast burritos; fresh produce from the Alameda County Community Food Bank. No one was required to prove they had a child to pick up a meal, and everyone could pick up multiple meals per child under 18. “Come out and tell us what you need,” Elmhurst Middle School principal Kilian Betlach said. “We have an abundance of food.”

Elmhurst is one of 12 locations around Oakland that together served 25,000 meals to Oakland students on Monday. And on Thursday, under more ominous circumstances, they did it again. Families were provided with enough food to feed their children to last through the weekend.

For Betlach, the principal at Elmhurst the past 8 years and an assistant principal at the school the three years before that, there is a sense of pride that the school is able to continue to serve students in the middle of a crisis. The meal service, he recognizes, is also “one of the few positive things anyone can point to right now” in a world where shocking and scary news seems to pile up by the hour.

“We know that schools are the hubs for a number of services, not just its core function which is to educate kids and get them prepared for college and career, but we also have this larger focus on social services, including food,” Betlach said. “So there’s a real happiness, and I think pride in our team being able to continue to provide that service for kids.”

At the same time, the crisis has cast a spotlight on the roles our society is asking schools to play for students, especially those from low-income families.

“When one of our biggest concerns about closing schools is that we have so many students who won’t have access to a warm, safe, dry place to be for 8 hours and won’t have food to eat,” Betlach said, “we really need to think about what the hell we’re doing in this country.”

A school like Elmhurst, where 94.5% of students are socioeconomically disadvantaged, exists to disrupt inequities. But the coronavirus has exacerbated inequities in our world, our city, our education system. Some Oakland families have parents with masters’ degrees who are working from home and making sure their kids keep up their studies. Other Oakland families don’t know where their next meal is coming from.

“Families that have that kitchen table that kids can get set-up on, that have that internet-connected computer, or multiple computers for multiple children,” Betlach said, “they have opportunities to access things that other families don’t.”

Betlach said Elmhurst has received support and are curating resources for different subsections of its population such as housing insecure, undocumented, food insecure. Elmhurst teachers are working hard to stay connected with students and provide them with learning opportunities.

While important, these are stopgaps.

“We need to be clear the work educators are doing to just try to keep kids connected to the content and learning is not in itself instruction, and does not replace it,” Betlach said. “So as we think about relief and support plans for an industry, we also need to understand that low-income kids in our community and kids who started off behind the curve, they’ve been disproportionately hit by all of this and we need to start to think about how we’re going to make this right for them.”