Holding schools accountable for educating our scholars

I’m frustrated. In education, the family dynamic plays a critical role in the elevation of our scholars, but the school environment and system share responsibility when our scholars are miseducated. When I say “our scholars,” I’m referring to Black scholars. If I don’t send my son to school or legally create a system where he’s receiving academic instruction, I receive fines, the loss of my driver’s license, and other consequences no adult would want. But if the school miseducated my child, what consequence does it receive?

Julian Bond once said, “Violence is Black children going to school for 12 years and receiving 6 years’ worth of education.” Violent acts have been committed towards our Black scholars in General Education and in the Special Education for years. Some are strategic attacks, but many are executed by those blind to the harm being done. I am not a specialist in the Special Education Department nor in education in general. I am simply a Black Educator who’s observant and takes action in my profession to contribute towards the success of the Black Excellence Movement. There’s clearly a difference between being a teacher who teaches Black scholars vs. an educator who teaches Black scholars to be excellent and are culturally aware of the mission they must accomplish for Black culture to thrive. This article is simply my therapeutic way of getting things off my mind so I can get back to being the solution.

What is California’s Williams Decision?

In my Language and Language Development class for UC San Diego’s Extended Studies Program, I was assigned a review of the history of bilingual education and asked to highlight one influential case, and discuss the implications of California’s Williams Decision. The Williams Decision established new standards and accountability mechanisms to ensure all California public school scholars have textbooks and materials required, and that their schools are clean, safe, and functional. It also took steps to make sure scholars were in the presence of qualified teachers.

As I read through the decision, I couldn’t help but wonder, “Did the decision of Brown v. the Board of Education (1954) negatively impact the current state of Black education, especially for Black English Language Learners and Black scholars who receive special education services?”

Has Williams negatively impacted California’s Black scholars?

The Williams Decision included components assuring scholars have qualified teachers. I absolutely agree California is exercising measures to ensure all teachers are qualified (hence my enrollment in Cross Cultural, Language, and Academic Development courses, to solidify the transfer of my Georgia Teaching Credential to California). Adults in leadership positions need to consider Black scholars when developing measures to ensure teachers and administrators are effective in educating them, as well as facilitating ‘culture fit’ interviews that demonstrate their competency and intent.

Before Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Black scholars were primarily in the presence of Black educators and administrators, who facilitated instructional environments that gave scholars a sense of belonging and understanding of the duty they must complete to thrive with a Black excellence mindset in a nation that benefits off of their ignorance.

Integration of schools took place, but are California schools with a large population of Black scholars being nourished with the services and resources to deliver quality education and keep proficient educators/leaders with talent proven effective for our scholars to fully develop?

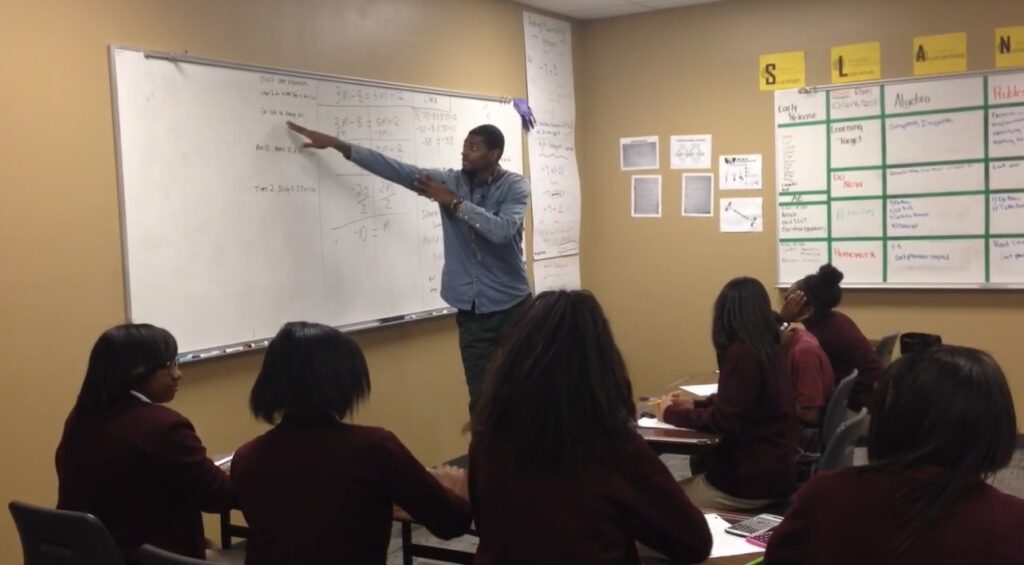

My experience teaching at a thriving Black school

When I think about ‘Separate but equal’ I compare my experience educating at Tindley Collegiate Academy in Indianapolis, Indiana, with Oakland, California. When I was there, Tindley had a student population that was 92 percent Black, 5 percent multiracial, 1 percent white and 1 percent Latino/a. Tindley was one of the city’s most racially isolated schools. With a Black dominant network and fiscal resources, Tindley Collegiate Academy was ranked second of top 10 charter schools in Indianapolis when I taught there in 2014-2015. Much credit to Kelli Marshall, as she set a high excellence expectation for systems and routine, educators, parents, scholars, and community.

Even for the educators who identified with non-Black cultures, they were still welcomed and praised for their work. They were trained properly and had an understanding of their role if they wanted to educate Black scholars. They listened and were receptive to feedback from Black educators, no matter the job description, because there was a clear realization of who lived the experience of those scholars being served at the school. If anyone’s view of education did not align with the school’s mission for Black scholars, regardless of vacancies, they would be professionally told that this job may not be the best fit for them. Mrs. Marshall’s philosophy was that having a missing piece was far better than having an incorrect fit to simply fill a role.

Why don’t we have schools like this in the Bay?

Since coming to the Bay Area, I have yet to find a similar environment holding adults accountable for educating Black scholars to be elite. Instead, I’ve found myself in spaces that provide Black scholars with sympathy and excuses to be average, while ineffectively being able to train teachers to maintain classrooms where high rigor instruction can take place. When it comes to reading data, please point me in the direction of a predominately Black school in Oakland that’s thriving so I can give them their praise and apply to work there. If you can’t find one, you understand my frustration, and why it’s irritating to witness schools that predominantly house Black scholars either not experience Black leadership with ‘Black Excellence’ systems, or starving of resources for them to compete at a high academic level.

How to contribute positive change in the state of Black education

Do our Black scholars receive a quality education? Do they receive adequate material that connects their culture with the academic standards required for them to complete? Do they have an understanding of what it means to be Black in America? Are they held to a high standard of achievement by their teachers?

There’s a lot of blind spotting in education. It’s going to take our allies to not only understand the role they play in the miseducation of Black scholars, but also know their strengths and take action on the feedback Black educator across the nation have been expressing. This is how to contribute to positive change in the state of Black education and for Black excellence to shine.

Much love to The Center for Black Educator Development, Watts of Power Foundation’s Teacher Village, and Black Teacher Project Oakland for their work in training and retaining Black educators.

MarQuis Evans, a proud native of Warner Robins, Georgia, is a multifaceted professional with an impressive trajectory in the education and entertainment sectors. As a Program Manager at Energy Convertors, he has effectively championed initiatives aimed at driving change within marginalized communities. He also contributes his expertise as a Content Specialist of Culture at KIPP King Collegiate, shaping and enriching the cultural ethos of the institution. His journey in academia commenced as a Math/Humanities Teacher at Tindley Collegiate Academy in Indianapolis, Indiana. This role set the stage for his subsequent position as a Financial Literacy Educator for 5th to 8th graders at KIPP Bridge Academy in West Oakland, California. This position underscored his commitment to empowering young minds through financial literacy.