A guest post from Dr. Brian Stanley, Black | Husband | Father | Leader | Policy Nerd | Oakland, we always welcome guest writers

The Oakland Unified School District is recommending merging my child’s school, Henry J. Kaiser Elementary and Sankofa Elementary into a single school on the Sankofa campus in North Oakland. Kaiser, nestled in the Oakland hills, has high test scores, wealthier families, and more White students. Sankofa is on its fourth principal in three years, is mostly African American, and 90 percent of its students qualify for free and reduced price lunch.

Some in the Kaiser community greeted this recommendation with resistance so intense it trickled down to my kids. Last spring, I was shocked when my boys came home from Kaiser repeating some of the fears they heard on the schoolyard. I reminded them that, “Those families at Sankofa are just like us. Those kids are just like you. And never let anyone convince you that someone, especially someone that looks like you, is somehow less than you.”

I support the merger at Sankofa because I’m excited at the possibility of co-constructing a dynamic new school community with Sankofa. While it’s far from perfect, Kaiser is a good school that my children have benefited from being a part of. I simply believe more families should have access to what the school does well and we should build on that with Sankofa to create something special for more children.

I’m also clear that Kaiser owes its existence and its success to Oakland’s deep history of educational inequity the has allowed schools like Kaiser to thrive and schools like Sankofa to struggle. If we cannot muster the will to interrupt this cycle in 2019 then it’s time to get honest about why. As Sankofa parent Subodh Nijsure succinctly put it, “…it’s all about race.”

Race, class, and educational opportunity in Oakland.

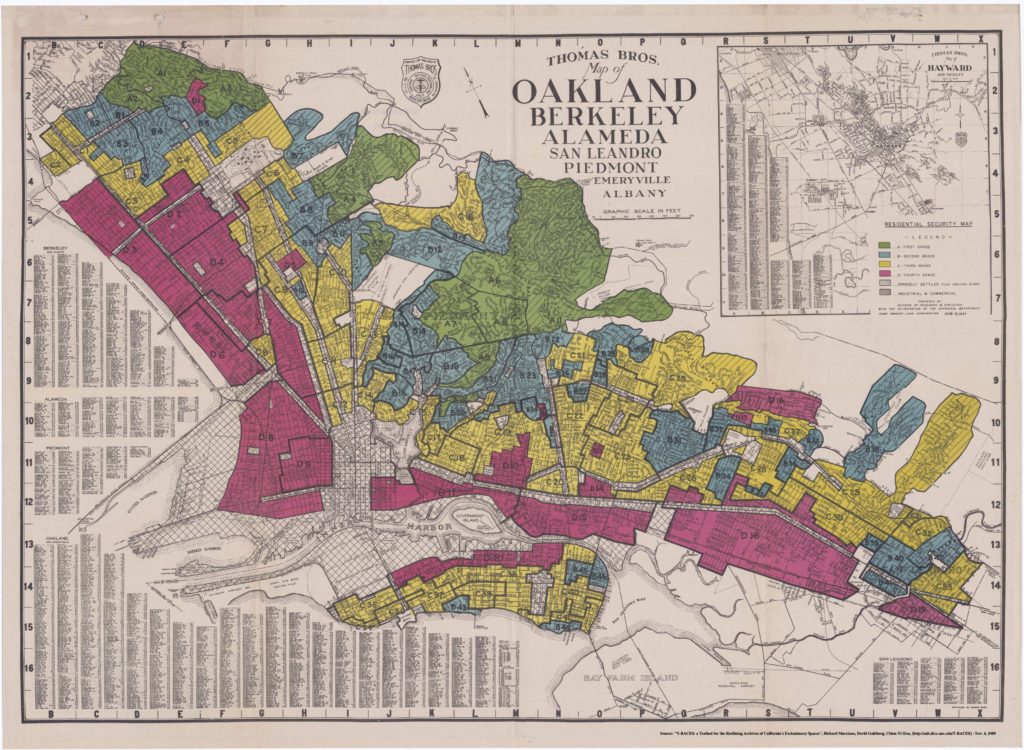

Today’s Oakland public schools reflect choices made by elected leaders in the 1960s and ’70s to protect the priorities and privileges of White families. Important choices — which neighborhoods got new schools and which didn’t, which schools were transit accessible and which weren’t, who could enroll in which schools and who couldn’t — were all resolved to reinforce the racial caste system deeply rooted in our society.

Seen in this light, today’s challenges are not new. Kaiser is merging because in the 1960s the district left overcrowded schools in Black neighborhoods and happily subsidized smaller, under-enrolled, and inaccessible schools in mostly White ones.

Kaiser is merging because the district failed to adequately respond to the White flight that formed the core of an enrollment decline from 63,000 in the early 1970’s to roughly 48,000 by 1980.

Kaiser is merging because for 40 years the Oakland Unified School District has steadfastly maintained nearly twice as many schools as it needs, creating a persistent fiscal crisis that limited opportunity for all but the wealthiest communities. Despite many well intentioned efforts to address these issues (e.g. small schools, charter schools, turnaround schools), our community is unable or unwilling to disrupt our two-tier educational system.

We’ve grown so familiar with this unjust system one could almost be forgiven for missing how well it works. First, so-called “hills schools” often attract wealthier families by virtue of their reputation as “good schools” and their location in wealthier neighborhoods. In a city where 74.4% of students qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, these schools often serve student bodies where 4 in 10 — and in some cases just 1 in 10 — students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. This concentrated wealth enables these schools to rely on substantial parent fundraising to pay for additional classroom support, resources for teachers, and co-curricular programming. These additional supports play a role in helping these schools retain their teachers longer which has been demonstrated to deepen student learning. Finally, these same parent communities deploy social and political capital to advocate for additional public resources and protect the most useful aspects of the status quo, thus ensuring that this concentration of advantage continues unabated from one year to the next.

Though this system benefits me as a parent, 30 years ago it crushed me as an Oakland High School student. My schooling was shaped by never having enough. We never had enough paper, supplies, or support. Our teachers weren’t paid enough, never experienced enough, and while most struggled to be their best, a few simply never tried enough. A handful of schools relied on thousands of dollars in parent donations to insulate themselves from our endless fiscal crises and provide “extras”, like art.

The worst part is this system not only denies a good education to kids who look like me but normalizes the result so well that the rest of y’all hardly noticed then…or now. Our city accepts that about 15% of Black males are reading at grade level in third grade. Our city accepts that 9% of Black males are proficient in middle school math by the end of 8th grade. Our city accepts that only 71 of the 288 (24.1%) Black males in the class of 2018 graduated eligible to even apply to the University of California and California State University systems.

These are not the schools any children deserve. Yet, these are the schools we give Black children year after year. To paraphrase Cornel West, the question we need to ask ourselves is: when exactly did we become so comfortable with injustice?

A fight worth having.

To be clear, merging these communities will be hard work with no guarantee of success. It will take more than yard signs, slogans, and good intentions to interrupt a system this exquisitely well designed. We need to contend with the graveyard of broken promises made to communities like Sankofa. We need to reckon with the political reality that asking families like mine — privileged families who benefit, in some part, from the status quo — to give up their comfort for the common good is always politically untenable. We need to confront a set of timeworn tactics ranging from endless calls for revision and reconsideration, to robust pressure campaigns on elected officials, to promises that teachers and families would rather leave than stay at the merged school. The result of these tactics, no matter how noble the intent, is to maintain an intolerable status quo at the expense of what could be.

If it’s worth fighting for, it’s a fight worth having- Senator Kamala Harris

I’m convinced that bringing the best of Sankofa and Kaiser together is the right thing to do even though it’s the harder thing. We don’t need to wait for perfect funding, perfect planning, or a perfect district. It’s time to start believing in the power of these two communities — families, teachers, and administrators —to build the school every child deserves. We can absolutely do this and it’s time to get to work making this happen…together.