A guest post from Thomas Maffai and Go Public Schools Oakland April 27, 2021

Haz clic aquí para leer en español

As part of our Numbers & Narratives: Year in Review series, we’ll be releasing new data reports and stories to better understand the toll of the pandemic on Oakland education, lift the experiences of families, and make recommendations to drive recovery efforts.

The staff at Life Academy in the Fruitvale know how important consistent student attendance is to ensure kids stay on track. So as the pandemic complicated teaching and learning, and students began to disengage, a team of teachers took responsibility for closely monitoring student absences all year.

“The pandemic actually pushed us to create better systems,” shared Life Academy Assistant Principal Ron Towns. “Our [intervention team] is one of our strongest teams now. That is the team that spent every week looking at which students are not showing up.”

Chronic absence is defined as missing 10 percent or more of school over the course of the school year for any reason, including excused and unexcused absences.With the shift to distance learning, OUSD redefined how students are counted as “present.” For example, a text message from a parent counts just as much as attending live Zoom classes, or submitting independent work. But the team at Life Academy still paid close attention to who was showing up to live instruction on Zoom and developed targeted outreach plans for any student that wasn’t logging on consistently.

When the intervention team at Life Academy dug deeper into the reasons why students were disengaged, they were often surprised by their findings. Many staff assumed that it was the spiking mental health crisis that was causing students to avoid Zoom, but home visits told a different story.

“When I talked to kids about why they weren’t coming to school 9 times out of 10 it wasn’t for a mental health reason but rather it was for an academic reason,” explained Towns. “[Students] just didn’t understand what was going on in class. They didn’t know how to use the Zoom or how to access the content or how to be independent learners.

“This should be a primary goal of high school: to support students to be independent learners. Before the pandemic we weren’t good at teaching kids those skills. Now that they are at a distance and they don’t have those skills, they crack.”

As some students at Life Academy began to disengage at greater rates during distance learning, the intervention team focused on the data, paying close attention to who was showing up to live instruction on Zoom and developing targeted outreach plans for any student that wasn’t logging on consistently.

“There were a few things we tried in terms of interventions. We would call home. We would host in-person family meetings if the family was comfortable or on Zoom to better understand the family’s challenges and problem-solve together,” Towns shared. “We identified social-emotional supports and connected students to teletherapy opportunities and we conducted quite a few home visits. We started an in-person learning pod specifically for chronically absent middle schoolers. And then I eventually started a similar version for high school students.”

Historically, high school students have faced the most barriers to regular attendance and the research is clear that students who are chronically absent are less likely to graduate. Some are pulled away from their own studies to care for younger siblings or are obligated to find work to support their family. While high school absence rates are typically higher than elementary or middle schools, this year they have soared. Across the district, more than a quarter of high schoolers are now chronically absent, and at some large high schools like Fremont and Castlemont, more than half of students are chronically absent.

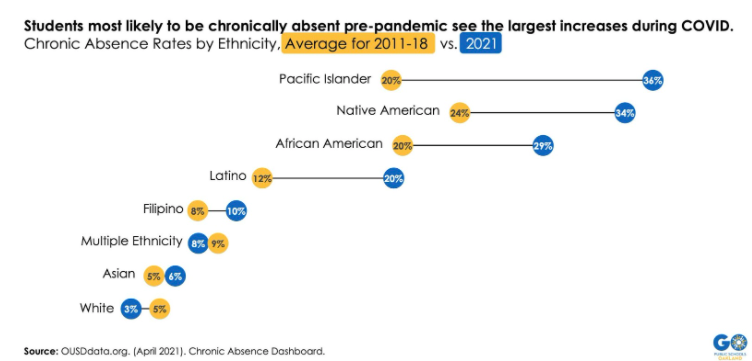

During the course of the pandemic, we’ve seen major disruptions to student learning and they are adding up — especially for high school students and those from certain racial groups including Pacific Islander, Native American, Black and Latino/a students. Most racial groups saw some increase in absences during this past year of distance learning, Native American, Pacific Islander, Black, and Latino/a students saw steeper increases. Black and brown students in Oakland tend to face more barriers to attendance than white students. On average, they report having less access to technology and often live in the neighborhoods hardest hit by the pandemic.

Even with a tentative agreement proposed for the return to in-person instruction in the fall and hope for an overall decrease in absences, the Life Academy intervention team’s work shows promise and clearly highlights the importance of finding innovative ways to reach students at all costs.

Leaders across the district recognize that connecting to students will be an ongoing challenge. According to Matin Abdel-Qawi, a district administrator who oversees high schools, students have already started to disengage and he fears they won’t be seen again.

“So we’ve put proposals out to hire community liaisons – people who are ready and willing to get eye-level with our kids, people who are ready to door-to-door and find our kids, re-engage them. We want to hire a group of people who are going to go deep into our communities,” said Abdel-Qawi.

Abdel-Qawi further explained that intervention teams, like the one at Life Academy, as well as data systems and dashboards are already being used across the district to identify students who aren’t connected. “We want to start the work now so that by the time August 9th rolls around we’re ready to receive [students] as scholars – even if that’s not how they have seen themselves this past year,” he said.

As Oakland educators and families approach the end of this year Life Academy 11th grader, Brian Burgos looks ahead to his senior year, he offers students a piece of advice to carry into the next school year. “I would say, start with your work from the beginning and don’t miss your work,” he shared. “Because if you get behind it’s hard to catch up.”