I worked with one of the top scoring charter schools in NYC. It was also one of the worst schools in the City. This school is a cautionary tale for the unceasing push to simplistic accountability formulas and how schools can manipulate the numbers while not really delivering the goods.

The school had the second highest proficiency rate for 7th grade math scores of any charter school in the City (93% passed), and also had strong ELA numbers. It was a middle school, so it makes sense to judge performance based, not where kids come in, but their status as they progress, and their preparation for the next level. So I looked at the highest grade served.

“No Excuses” run amok

The school was also cited as having the highest attrition rate in the City, with 31.7% of students leaving in that year, and similar attrition in the prior ones. The school had also failed to return a single classroom teacher in either of the first two years.

It was “no excuses” run amok, for the kids and teachers. There was an early report of bathroom graffiti, so the bathrooms were closed except for a few times during the day. The staff reported to me with some strange self-satisfaction that a student had gone to the bathroom on herself, because of these closures. With a quip around “that will teach them to take care of the bathrooms.”

Kids were suspended all the time, and many parents left rather than facing the punishments. The school had a 28% suspension rate—so more than 1 in 4 students were suspended in a given year.

Teachers were similarly worked to the bone. Because of the constant staff departures, there was always a need to cover classes and most teachers worked from breakfast to the end of the school day without a break.

A similar harshness in dealing with the staff prevailed. So much so, that the teachers voted as “teacher of the month” a colleague who had been fired the previous month. I would call that a morale problem.

I know that someone is thinking they cheated on the tests. They didn’t. They “cheated” on their student population. Like so many schools do. Let’s dig in a little though.

How did this happen

The school was a charter school with a lottery for admission and freedom to set its own policies. It was located in a largely low income neighborhood, with many first generation Caribbean immigrants. Many highly motivated families, even if they had not achieved the American dream for themselves, they were supremely hopeful for their children, and worked with them and pushed them hard. Many families were accustomed to relatively harsh conditions and showed what might be called “tough love” to their kids. I am speaking in overly broad stereotypes but stick with me. And there were certainly some families who appreciated the rigid discipline and “no excuses” culture.

But many more didn’t. And roughly a third of the school voted annually with their feet to leave. But these were not the average student, low achievers, English learners and students with special needs left at higher rates. Parents that were frustrated with the lack of responsiveness or services would leave. Or those facing what they saw as unfair punishments or conditions would just withdraw their child rather than continue to be subjected.

And here’s the kicker, in order to be promoted from grade to grade you needed to pass your classes and show proficiency on the State test, by scoring a “3.” While in the traditional department of education schools and almost every other charter you only needed a “2.” So students faced with repeating all of their classes at this charter school, or withdrawing and attending a different school, would always just leave.

Shit, I would leave if that’s what the school told me. That my kid had to sit in the exact same classes for another year, I would get his file walk downstairs to the DoE school and enroll him. So, to sit for the test in year 2 you had to show proficiency year 1.

I also have to add that the school did have a great math teacher that year, who did hold it down with the kids that had made it to 7th grade, and did a great job teaching them. So it wasn’t all smoke and mirrors, but some of it was. But those most challenging kids, or those that started 5th grade far behind were either gone or hadn’t advanced to the 7th grade. And by year 3 there were no special education students in the 7th grade at all.

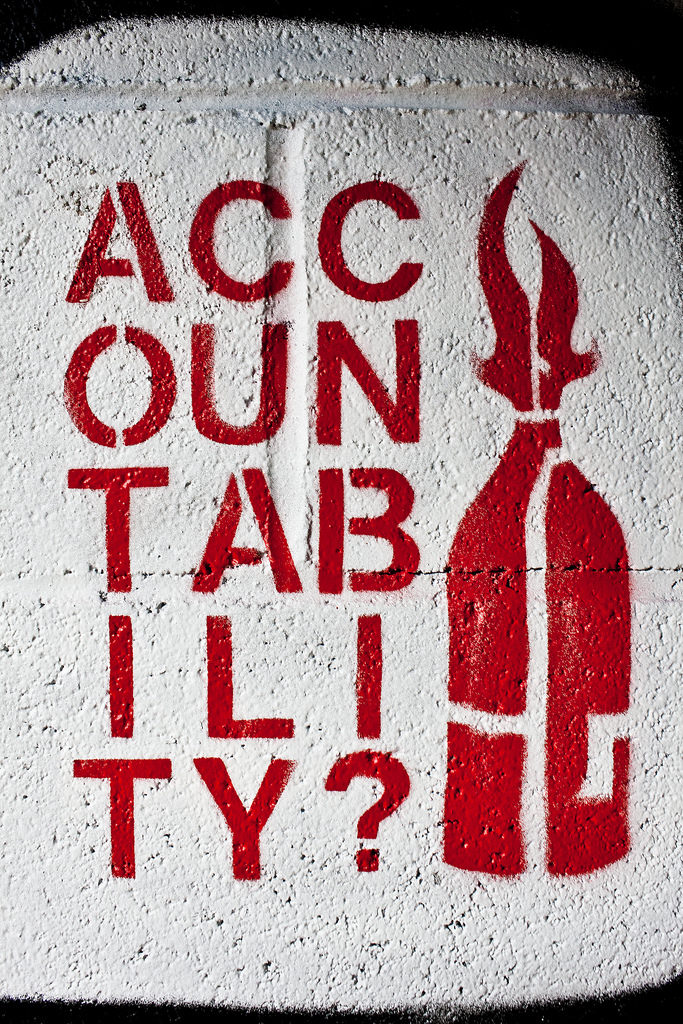

Lessons for Accountability

I am the accountability guy. Schools are there to increase student learning and social development, if students aren’t progressing or subgroups of students are stagnating, we need to look hard at what is happening, and whether other answers might be needed. But the way we tend to judge school accountability—by looking at proficiency levels of students as the key indicator—misses student growth, and can distort the overall picture.

Student attrition and the composition of the student body are crucial factors that are often missed when we look at school quality. Again I remember the old days of test prep, where the rules distorted school’s instructional focus. Where the schools energies were targeted around that minority of students on the cusp of moving up or down a performance level, because that was what was measured and valued for “accountability.”

So if a student needs 75% correct answers to be proficient, then all energy would focus on those students in the 70-80% range on the pre-test, those who might slip just below, or those that might climb just above the bar. And for the focus put on them, focus was taken away from students who weren’t close or likely to sit on the cusp of a cut point.

That is basically how we have looked at accountability in California for the last couple of years, looking at pure proficiency scores. And it doesn’t necessarily tell us much about school performance. It may, but it may not.

Thankfully the California State Board of Education has improved this process. We are making some progress here with updates to our accountability system, which EdSource is doing a good job covering. But we still have a ways to go, both on some the details of the measures, as well as making them accessible and useful for families.

And there are a range of small technical decisions in the accountability formulas being made that will, determine whether accountability really measures the value schools are adding or whether it creates a set of data points that nimble schools can game. We will be keeping our eyes on these decisions, and hope that you will too. The devil will be in the details, and it will be up to us to catch and exorcise demons, before they haunt another generation of California’s children, obscuring school quality and rewarding cheaters, rather than informing parents and identifying the virtuous.