How does a school community react when a student threatens extreme violence? This inspiring guest post describes how we can build better communities amidst the fear and struggles. This a true account of a real threat that took place at an Oakland school. Names and school identifiers have been changed or removed to protect the safety and wellbeing of involved parties.

Like a small wildfire, the word passed from students to after school instructor to me as an administrator in a matter of minutes. We were standing in the lobby after school had just let out, and a large group of students was huddled wondering who was on the other end of the threat. Were we all in danger? Was it real?

Someone had hacked into Instagram accounts and was sending fake messages impersonating different students and staff. The individual began in a teasing manner. These messages became violent, hateful and threatening in nature, as they were laden with hate speech with regards to sexual orientation and, at multiple points, encouraged students to stay home from school because the person was going to “shoot up” the school the following day.

Trying to find the “shooter”

We immediately began our emergency responses and school investigation, and worked late into the night, interviewing students and families who had been contacted or interacted with the fake accounts. In my experience, students will share or take ownership when they realize the seriousness of a situation or that they have really scared or hurt others. This didn’t happen. At 9 pm, the decision was made to close school the following day.

Myself and another school administrator and office staff went in early the next morning to continue meeting with students and families, taking statements and trying to piece together what was going on. Our calls to Oakland Police Department didn’t immediately prompt action on their end. We called the San Francisco FBI office and shared the threat, and within minutes had city officials and high ranking OPD members at our door. At the end of the first day of school closure, we still didn’t have enough information and had to close the school a second day.

Juvey or justice?

Over the following weeks, we worked closely with a team of investigators, and they ultimately were able to obtain information through a search warrant from Instagram that identified the individual who was hacking the accounts. In many cases, this would have been the end of the conversation on the school end. The individual would have been charged and put through the wringer of the criminal justice system. At least seven different California Ed Code violations, including making terroristic threats, were at play. The student would have likely been expelled from school and placed into the juvenile detention center pending more serious charges.

As a school, like many schools in Oakland, we espouse a restorative approach to discipline. I’ve personally facilitated hundreds of conflict resolution and restorative agreements between students, adults, staff members and outside organizations. The seriousness of the threat and fear that I felt taxed my belief that the restorative approach was the avenue to take.

“We Believe in Restoration”

After a large community gathering where more than 300 families came to listen and voice their thoughts, we made a decision to not move forward with pressing charges. We wrote in a letter to the student and family, “… we believe in restoration when harm is caused, and we avoid adding children to the judicial system if at all possible. It is out of this deep moral value and the confidence bestowed in this known family that we offer you a restorative agreement in place of pressing charges through the judicial system.” We worked extensively with the student, family, the students’ school and our community to build a process that worked to repair over the course of many months.

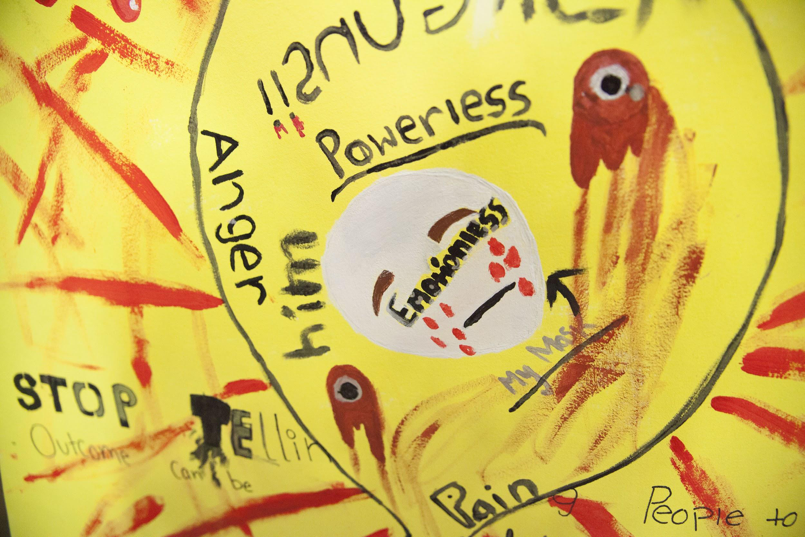

There was a lengthy suspension, as restorative practices and school policies don’t need to be mutually exclusive, and lots of community reparation involved. This is an excerpt from a draft of a letter the student wrote (and as an educator, the student wrote and rewrote multiple times).

I want to write this letter of apology for what I did. I am very sorry for causing a false panic and for having the school lose money. I was being stupid and not realizing what would happen. I meant no harm to anyone. I do not own any weapons and I can’t even walk around Oakland by myself. I apologize to the teachers and staff because I made them lose out on money. I apologize to the parents who were scared to send their kids to school and also to the kids who had stress or anxiety. I’m sorry for what I have done and regret my actions. I realize my actions were stupid and irresponsible. To make up for this I will be working closely with the school staff as well as my current school doing community service around the schools.I am hoping you can forgive me for what I have done.

In an era when some politicians believe that school safety is about arming teachers with weapons, and no excuses schools perpetuate the criminalization of youth of color, it can be increasingly difficult to enact restorative and transformative practices. When our district cuts funding to programs and staffing for RJ, there seems to be little alternative. When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

The school to prison pipeline is alive and well in this country, and all of us as educators, no matter what our role, can shift the trajectory for black and brown youth.

When a five year old calls another student a name, or a game of tag escalates into a wrestling match on the recess yard, or a student “disrupts” instruction by calling out, the response from the adults and institutions is critical. It can focus on what rule was broken and “assign” the appropriate consequences, or it can go deeper to use discipline as an opportunity to teach and repair.

We can raise our babies with love and help break the pipeline if we choose to do so. It takes time, collaboration, meaningful relationships, patience, and tools other than hammers. It takes proactively building a community and seeing everyone as a vital member. If there isn’t an established community, there isn’t going to be anything to restore. For educators, it means investing the time to really get to know our students, families and colleagues, and building a school where love is at the center.

For more information about restorative practices, check out:

- Growing Fairness: a documentary about growing restorative practices in public schools

- RJOY: Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth offers resources and training

- International Institute for Restorative Practices: an international organization with professional development opportunities