| A guest post from James Harris, former OUSD trustee, who has started a really interesting blog that you should check out |

I have been trying to figure out a way to talk about school board policy in a way that doesn’t put you to sleep. In fact, I’ve been avoiding the topic of policy altogether because who— really— has time to talk about policy with everything that life brings? But, if I can steal five minutes of your time, I do want to talk about the road to the adoption of the Community of Schools policy by the Oakland School Board in 2018 because I think it really illustrates some of the nuanced elements of the district run vs. charter school divide that I wrote about in my last post. I’ve pasted the full policy at the bottom of the page for those of you who care to read it in full. Being a nerd of sorts, I think it’s worth a peek.

The road to the policy’s construction and adoption was about six months long. It was controversial when I first introduced the idea, and that controversy lasts until today. I think most of the drama was about one statement in particular: “The Board recognizes that it has oversight over all Oakland public schools, both those run by the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) and those run by various charter school operators.”

What seemed obvious to me when I drafted the first version of the policy was that all of Oakland’s public school students are our responsibility no matter how they come to us, in district schools or charter schools. However, it was this single declaration that nearly derailed the policy’s adoption and exposed the true division that exists in Oakland between district school supporters and charter school supporters. The truest supporters of district schools say that charter schools drain the system and prevent growth and charter school supporters say the district system is broken and its their right to exist as a means to fix it.

What I am writing about today is the history and circumstance that led me to write the policy and make such a declaration in the first place.

I’m From the Government, And I’m Here to Help

Remember, that OUSD was taken over in 2003 and run by the State of California until 2009, when it was returned to local control. Remember, too, that in an effort to drastically accelerate student outcomes, during the takeover, the state— either consciously or subconsciously— embraced a hybrid public school model where charter schools were introduced en masse and added to an existing collection of newly redesigned small schools, developed by the local school board in 2000, to create a more intimate and flexible setting for students to get deep engagement experiences.

In the early 2000s, these small schools were fueled by huge interest from the Gates Foundation and sparked innovation and redesign at East Oakland schools like Castlemont, Elmhurst, and Stonehurst. The charter sector also began extremely rapid growth during this period. According to KQED data, the state of California also approved 32 charters from 2003 to 2009. With the charter growth, and by breaking schools like Castlemont into three different schools and Elmhurst into two campuses and Stonehurst into two small schools, when the collective movement was done, the district’s portfolio had grown by more than 40 schools in a seven year period.

This was a period of drastic innovation in Oakland. I think its something the city should be proud of because it was highly collaborative and many say the city was finally talking about education in a meaningful way. But what was never addressed was how this system would be managed, and more importantly, was it fiscally sustainable?

During the takeover, the State also took out a loan of $100 million dollars. The State did not assume the cost of the loan. That responsibility was left for Oakland to manage and pay. And until today, Oakland still writes a check for $6 million each year to repay that loan. The loan, as the State put it, was to help Oakland recover from the deficit that drove it into takeover in the first place, and to help it manage its budget going forward.

The charter schools that were established, and renewed over the years since their creation have grown in size and student population. In 2000, charters were around five percent of the school type in Oakland, now they make up nearly 30 percent of Oakland public schools.

When it comes to the Gates money, journalist Katy Murphy wrote it best in 2009: “The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which funneled millions of dollars into the effort, has shifted its national focus from small schools to high school reform. The $25 million that fueled the Oakland school district’s bold reinvention has run out.”

So after less than a decade, with Gates gone and the true challenges of the small schools movement fully exposed, the school district gained local control of a new type of school district— (I believe) the first of its kind in California. Not fully aware of the challenges ahead, the school board did what we do in Oakland: jumped in and started working.

I think the state was right to try various forms of innovation. I think that innovation and competition, if done with rules and regulations, can be good for students. But with no quantifiable thought about how it would all work and how a local school board would manage this hybrid infrastructure, and with California student funding among the lowest in the country, this chaotic beginning could only lead to us fighting for crumbs. And so, even after the Millionaire’s Tax of 2014 pumped millions more into both district run and charter schools, OUSD has had to make more than $60 million in cuts over the last four years and has had to close and consolidate schools since 2012 in pursuit of quality and to keep up with fiscal demands. Now doubly impacted by the pandemic and ongoing budget challenges, OUSD and charter schools are on pace to make more cuts in the future. It’s all dependent on what the State and Feds can do to mitigate losses and cuts. But one thing is for sure: teachers are underpaid and true quality schools are still hard to come by in some Oakland communities.

So, in the end, I believe that the district-run vs. charter school conversation is completely shortsighted. This has been the landscape for about 14 years— and it wasn’t a locally elected school board alone that built it.

In truth, district and charter schools are in a small boxing ring, created by historic circumstances, fighting for limited resources and inadvertently perpetuating inequity. We must stop the fight, stop pouring unnecessary money into a quarrels about governance structure and school type, and work to properly fund all schools and teachers to do the work, and take strong action that empowers both district and charter schools to collaborate and effectively educate our children.

Reflection

It was the history above that informed my decision to write the policy. I knew we could not undo the history. I also knew what my heart was telling me: that our tax dollars don’t discriminate. In fact, they are there for every public school student no matter if they attend a district school or a charter school. I knew I could not fix or erase the history that got us here, but I knew I could try to help us change how we think about the challenge going forward.

I think the adoption of the Community of Schools policy is one of the noteworthy moments for Oakland schools. In response to the damage done by California’s state receivership and the flooding of a portfolio of schools that could never be properly managed, (in my opinion) the Oakland school board— in the adoption of this policy— started to take accountability for all Oakland students and put itself on the hook for the organization and management of those schools, despite the history. In a lot of ways this act of acceptance and tolerance feels like what Oakland is about. Hell, this feels like what America is about.

Some of the small schools, which were district run innovations, were able to achieve short term success; at schools like Acorn Woodland and Encompass, success persists today. But most other small schools were reassembled back into larger schools after local control was regained, but some continue to underperform today. Among the cadre of charter schools, there were successes as well, among them Lighthouse Charter School and Oakland Charter Academy, which in 2007, became the second public school in Oakland to win the National Blue Ribbon award.

I say this because there are charter schools in Oakland that are doing remarkable work and have proven themselves fit for the fight to improve academic outcomes. I believe these are trusted education partners, committed to Oakland. This is not because I declare it, but because of their track records of success.

There are schools of both types doing excellent work, some of them parts of innovations that came during the state takeover. Oakland parents are proud to send their children to Coliseum College Prep or Oakland Tech or Edna Brewer or Aspire’s Berkeley Maynard or Oakland School of the Arts. I won’t name them all, but the point is that I believe that we have to be in blind pursuit of quality schools, no matter the denomination.

There are also charter schools and district schools that are not making the grade or delivering the results our students need. And if they cannot be fixed, they should be closed, redesigned, or repurposed for some community benefit that helps Oakland improve. End of story.

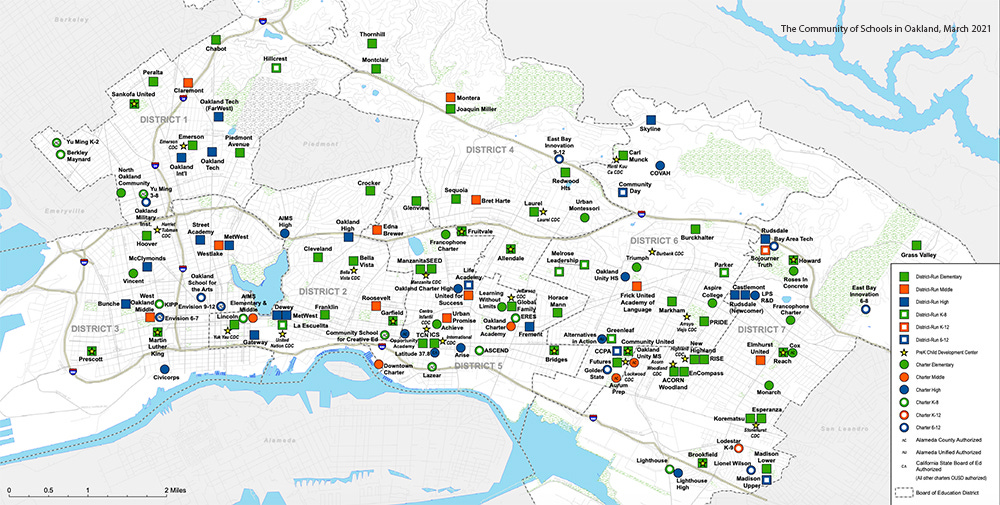

The fight about governance structure will continue, but at least now the Community of Schools policy has provided one idea, and perhaps a baseline, for how that fight takes place, and it highlights the true landscape of the school district the state created: a public school system with about 70 percent district run schools and 30 percent charter operated schools.

In the blame game, we can say the school board has perpetuated the growth of charter schools, but when you look at the data, the number of charter schools has been roughly the same from about the end of state receivership to present. The state helped create a confusing, yet remarkable system, but it’s up to Oakland to manage it.

Extra Reading: The Policy

Quality School Development: Community of Schools (2018)

The Board of Education (Board) is deeply committed to the vision of Oakland being home to high quality public education options for all students and families, no matter their race, ethnicity, zip code or income. To realize this vision, the Board directs the Superintendent to develop a citywide plan that promotes the long-term sustainability of publicly-funded schools across Oakland that represent quality and equitable educational options.

The Board recognizes that it has oversight over all Oakland public schools, both those run by the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) and those run by various charter school operators and also acknowledges that it has a fiduciary responsibility to maintain the fiscal health and well-being of OUSD and its schools in order to provide a high-quality education to its students. The Board also recognizes that this is a competitive landscape with limited resources, and the OUSD Board and each charter school board is working to ensure that each student has what they need to succeed. Still, it is the Board’s categorical expectation that all education providers operating or desiring to operate school programs in Oakland – district or charter – as well as families, staff, community members and labor unions, will accept shared responsibility for the sustainability of our school system and embrace the idea that we: (i) do not operate in silos, (ii) are interdependent in our efforts to serve all students and families; and (iii) need to act with consideration of the larger community of schools. We also recognize the challenging work ahead of building and rebuilding trust among the diverse members of our community in realizing this vision.

The Board is acutely aware of the legal constraints that limit its formal authority. Current state law does not currently allow the Board comprehensive authority on the location, authorization, oversight, and management of charter schools in Oakland. However, the Board is committed to establishing more high quality school programs and understands that this vision will not come without fiscal, legislative, and political challenges. The Board is prepared for the journey ahead and is committed to advocating for legislative changes that will result in greater and more effective control of the regulatory environment in which the school district operates.

To this end, the Board authorizes the Superintendent to increase access to high quality public school options for the students and families of Oakland using quality, equity, utility, sustainability, and community benefit* as guiding principles and factors during the redesign and reconfiguration of the OUSD that builds upon the current work of the Blueprint for Quality Schools process. This redesign should consider all OUSD-run schools and charter schools authorized by OUSD and Alameda County.